“Serbia Against Violence”: Protesting National Culture

The history and culture behind the Serbian protests against gun violence and nationalism.

An ordinary Wednesday morning scene: the sun rising, employees clocking in, children going to school. By the bright-and-early hour of 9 a.m., eight of these children are shot and killed. Not 36 hours later, another shooting strikes two towns in Belgrade. These last few months have seen mass protest not only in Serbia, but with the Serbian international diaspora as well. It has been one of the nation’s most tense periods in the 21st century.

Huge demonstrations have filled the streets of Belgrade, Serbia’s capital city. They demand the resignation of important politicians, gun control policy reform, and modifications to Serbian media, all of which they believe has fostered a culture of violence.

Many of these protestors argue that the culture of violence is rooted in nationalist thought and media which celebrates criminal life from during the nationalists’ strongest era. These claims are thought-provoking, especially given the region’s rocky history— namely, the decades of war from which Central and Eastern Europe are still reeling.

So what exactly is behind the growing popular resentment of Serbia’s nationalist culture?

Let’s begin with the stories of each event.

The Belgrade School Shooting

On 3 May 2023, at 8:30 a.m., Vladislav Ribnikar Elementary School’s daily routine was disrupted by 13-year-old Kosta Kecmanović opening fire inside of a classroom. One student who was present relates the chilling story through her father, Milan Milošević, who describes that Kecmanović “first shot the teacher and then started shooting randomly.” Another witness recounts seeing “kids running out from the school, screaming.”

“Perhaps the most horrifying experience I have had as a doctor and as a human being.” — Minister of Health Danica Grujičić

Owing to the rarity of events like this, the school drew immediate federal attention. Minister of Education Branko Ružić called a three-day period of mourning, and Minister of Health Danica Grujičić lamented it as “perhaps the most horrifying experience I have had as a doctor and as a human being.” Interior Minister Bratislav Gašić kept tabs on the aftermath, noting that eight children and a security guard were killed. Another six students and a teacher were injured. On the local level, Belgrade’s University Hospital treated three students and one teacher. One of the students later succumbed to her injuries. Local investigation by the Belgrade police force revealed a shocking truth: that Kecmanović had been planning the shooting in detail for at least a month prior.

Authorities uncovered hit lists and detailed plans of attack. The gun used was Kecmanović’s father’s, who had improperly secured the weapon in a safe. Mr. Kecmanović has since been detained for grave acts against public security, a criminal proceeding still under investigation. Authorities fault him for training his son in the usage of firearms.

Kosta Kecmanović’s justification has been one chilling sentence: “I shot because I am a psychopath.”

In the wake of these findings, protests against the government’s failure to act began to stir. The next day, however, only magnified these demonstrations.

The Mladenovac and Smederevo Shootings

21-year-old Uroš Blažić returned home to his cottage in Šepšin after an argument with his friends at a Mladenovac football stadium. But he did not stay there for long. Taking an assault rifle, three pistols, and four hand grenades, he expressed his rage via a drive-by shooting. His first destination was a village in Smederevo. There, Blažić shot 11, killing five and injuring six. He then continued to a town in Mladenovac, killing another four and injuring a handful of other civilians.

The subsequent manhunt took the region by storm. The Serbian government engaged 600 members of the Special Forces, an anti-terrorism unit, a helicopter unit, and Belgrade and Smederevo’s municipal police forces. After several mistaken arrests, authorities finally captured him during the morning of 5 May.

In the wake of Blažić’s arrest, investigations have uncovered shocking details. He was arrested wearing a shirt printed with the slogan “Generation 88 on Tour,” a pro-Nazi symbol.

Further examination into his social media accounts garnered that he was an ardent idolater of gangster and convicted criminal Kristijan Golubović, who was most active during the rise of Serbian nationalism in 1989–1997. Golubović exemplified the explosive tendencies of many Serbians during the period’s deep economic and cultural turmoil.

Moreover, Blažić’s family had a long history with weapons and military. His father, grandfather, and uncle, the latter two of whom harbored him during the manhunt, all owned diverse weaponry, including guns, ammunition, and explosives. His father, a former military man, has been detained. Authorities also arrested his grandfather and uncle.

During his questioning, Blažić repeatedly yet ambiguously referred to humiliation, disparagement, and being taunted as the impetus for the massacre. It is believed, based on his classification of his actions as “society’s injustice reflected onto me,” that Blažić fired to release pent-up rage about how society treated him.

Link to Nationalism

Some protestors fault nationalism fostered by the Serbian government as the cause of these shootings. They target certain features of the shootings, including widespread gun ownership, motivations, and Serbia’s historical culture of violence.

One of the more prominent justifications for this claim particularly lies with Blažić. A common theme of any nationalist sentiment is its obsession with reconciling “humiliation.” Take, for example, the white supremacist notion that the white race has been disparaged by racial integration (“white genocide”), and that the necessary recourse is to exterminate or otherwise force out those other races.

In this sense, Blažić’s upset over “society’s injustice” is in line with nationalist ideas of securing one’s identity via outbursts of violence. His fanaticism over Golubović follows in those footsteps. Golubović repeats that tendency of using violence to release frustration at humiliation — in his case, the economic and cultural instability of Serbia during his career.

The above image also underscores that some Serbians idolize violence. In particular, the artist of that song seemed to believe that including a renowned gangster in his video would make it cooler, hinting at the romanticized view of violence to some parts of the culture.

The nationalist obsession with violent reconciliation with past defeat saw its first spike in the 1990s, during the Yugoslavian Civil War. A minority of militant nationalist Serbians committed mass atrocity against those they saw responsible for their historical humiliation.

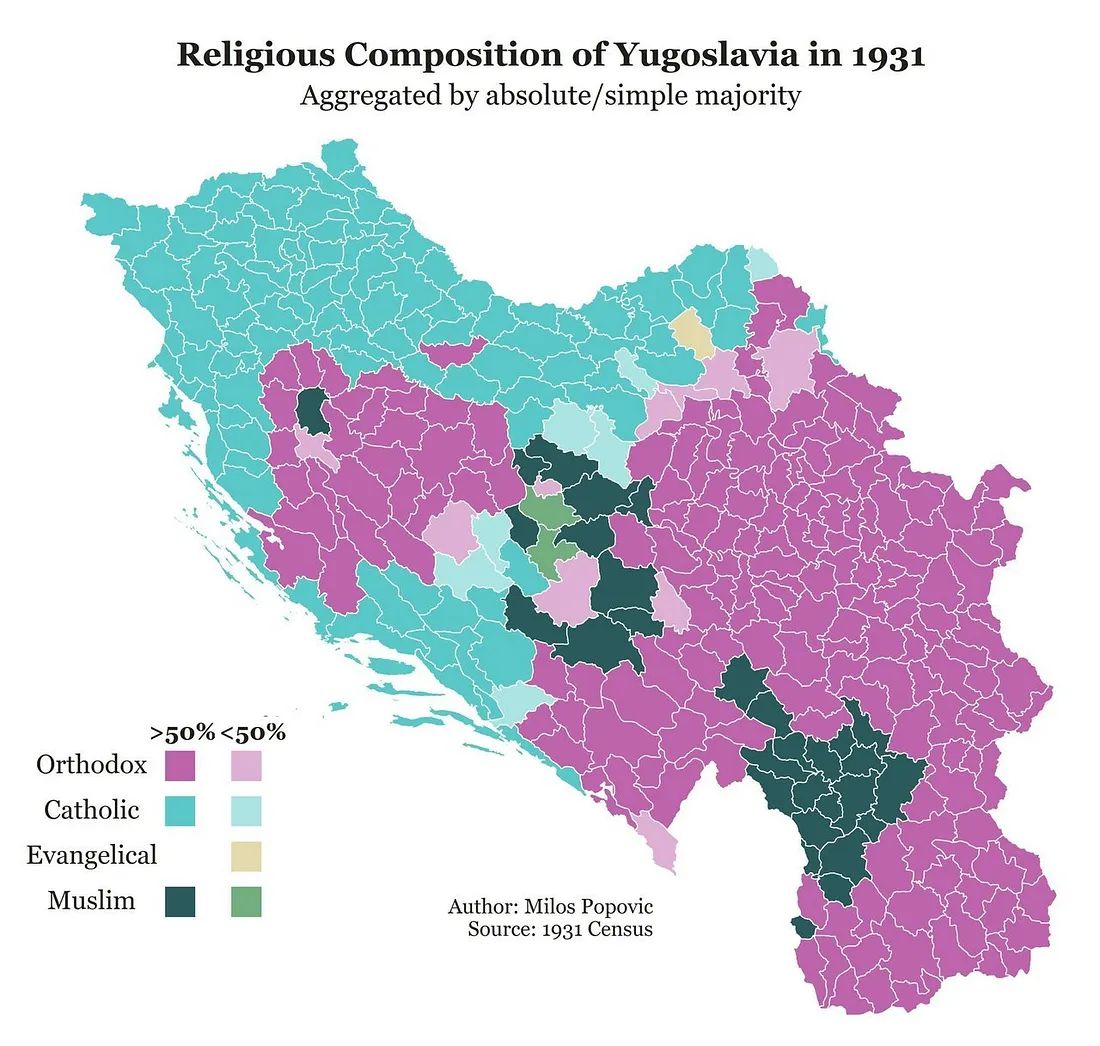

Josip Broz Tito established Yugoslavia in 1945 to unite the ethnicities of what is now Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia under one national banner. Leaders also carved two smaller autonomous provinces out from Serbia based on their ethno-demographic differences: Vojvodina in the North and Kosovo in the South.

Vojvodina had a uniquely large Hungarian presence, a remnant of its former ownership by the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As for Kosovo, its population was majority Albanian, who were Muslim by virtue of Ottoman conquest centuries before.

Tito ruled Yugoslavia for the next 35 years with an iron fist. A principled authoritarian with preserving the union at the forefront of his mind, he struck down any hints of nationalism from any ethnicity, a policy he dubbed “Brotherhood and Unity.”

Despite Tito’s efforts, some radicals among the ethnicities would never let go of their inter-ethnic enmity. This issue was especially rampant among Serbians, whose former conquest by the Ottomans left them a residual distrust of Muslims.

Distrust was not a new sentiment during Tito’s Yugoslavia. It was a remnant of an ideological policy in 1st Yugoslavia, established by Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia in 1918 after the Ottoman Empire’s dissolution. The policy officially “considered Muslims as the heir of the Ottoman occupiers in the Balkans.” 1st Yugoslavia, as a Serbian-led state, thus ingrained Serbian nationalists with a mindset that otherized and demonized Muslims.

Paralleling Uroš Blažić, who expressed violence as a recourse for injustices committed against him, Serbian nationalists were brewing violent ideas as recourse for the Ottoman conquest of Serbia. In addition, Serbian nationalists felt unseen by Tito’s anti-nationalist government.

So when Tito died, he left a gaping hole in Yugoslavian ideological policy. The provinces began to adjust to the realization that in absence of Tito’s iron fist of brotherhood, nationalism had a space to grow, fueled by the unshakable negativity that radicals had towards the other ethnicities.

The nationalists’ first opportunity for recognition surprised them on 20 April 1987. To calm the stirring ethnic tensions, Serbian President Ivan Stambolić was called to Kosovo. But Stambolić deferred the visit to his right-hand man and the to-be notorious Slobodan Milošević.

Milošević repeatedly condemned the nationalist hatred brewing between ethnicities in Kosovo and stressed the importance of maintaining peace to the union and its progressive Communist goals. But in agreeing to open dialogue with nationalists who expressed upset at his speech, he unknowingly committed to a position antithetical to Tito’s policy of “Brotherhood and Unity.” Where Tito, iron-fisted as he was, would have simply crushed the sentiments, Milošević provided the nationalists with a direct channel to the government through which they could get their ideas.

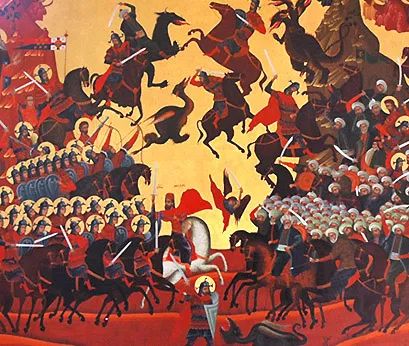

To Milošević, Kosovo was Serbian territory through-and-through. He perceived it as the center of Serbian history, taken from them in the 14th century when it was conquered by Muslims. Now called the “Kosovo Myth,” Milošević and many Serbian nationalists bought into the idea of ancient Serbian heroism in its last stand before defeat by the Ottoman invaders. And though most Serbians were forced out of the region by those invaders, the remaining ones appealed to the motif of injustice and humiliation.

It is from this story and its idolization by state television that Serbia’s small-but-potent warrior “cult” arose. Nationalists’ faith in Serbian heroism spilled over into a past-oriented perception of their ethnicity as martyr-warriors. Therefore, they transformed their defeat as a call to action for those who identify with the semi-mythical Serbian warriors. That loss — its humiliation — they asserted, required violent uprising as recourse. This echoes the logic of Blažić, who fired as an expression of rage against the societal injustices committed against him in his youth. And indeed, it haunted Serbians into the 20th century.

In their decisive meeting with Milošević, Serbian nationalists complained of mistreatment under the Croatian Ustaše and discrimination in Kosovo by the Albanian Muslim majority. The result was Milošević vowing to protect ethnic Serbians, aligning himself with the nationalist cause.

Hence, the culture of violence that plagues radicals in Serbia today. It is important to recognize that Serbian nationalism is unpopular today. But the idea of violence still stands. It’s apparent especially in the case of Uroš Blažić, who idolized violent gangsters as “warriors” in a period of stagnation, subscribing to the nationalist idea of violent vengeance for injustices committed against him.

Kosta Kecmanović, the school shooter, is a more difficult story. Evidence suggests that he was merely a psychopath, without any concrete evidence that he felt mistreated by the school. He did draw up a detailed hit-list, suggesting that he disliked specific students. But at the time of writing, I cannot be sure that this corresponds to him seeking out violence as revenge.

So in Kecmanović’s case, we have to look to the gun ownership issue.

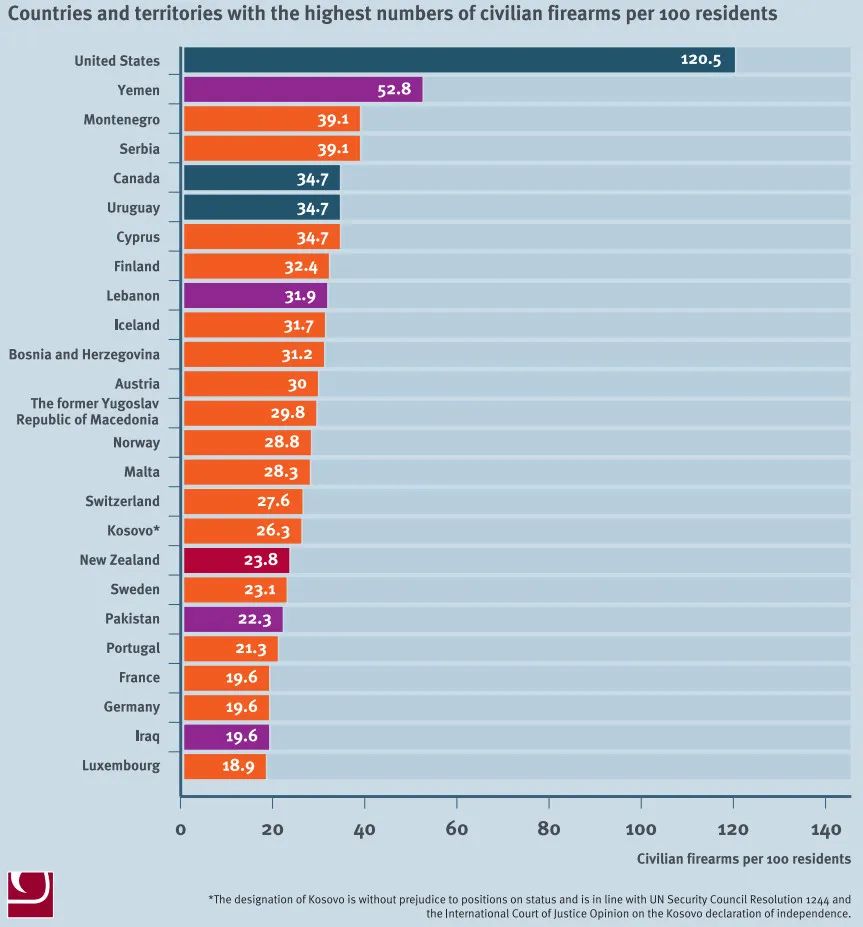

Part of the reason Kecmanović was even able to get his hands on a gun in the first place was because of its proliferation throughout the nation. Serbia’s per-capita civilian gun ownership is the (tied) third-highest of any nation in the world, at 39 per 100 population. It is behind only Yemen, at 58, and the United States, at 121.

Such a high statistic is intertwined with the Yugoslavian Civil War. When Milošević pledged allegiance to the Serbian nationalists, he became part of a broader set of conflicts in Yugoslavia. The rise of Serbian nationalism was one of the major elements of the Yugoslavian Civil War, which began in 1990.

Nationalists finally had their violent recourse for past humiliation. Vengeance appeared in tragedies like the Bosnian Genocide, where militant Serbian nationalists killed more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims on the basis of their ethnicity and religion. To many nationalists, it was a form of revenge against Islam, Serbia’s former conqueror.

Similarly, violence between Croatians and Serbians was widespread, perhaps recourse for mistreatment of Serbians in Bosnia and Croatia under the Croatian nationalist Ustaše.

During the broader war, weapons proliferated. The highly personal nature of ethnic conflict meant that many thought it was necessary to own weapons. Most of this ownership was for self-defense, but various militias and militaries — particularly the Serbian ones which appropriated the former Yugoslavian bodies — needed them for offensive endeavors.

Still, many of the weapons in ownership were and are hunting rifles. The remaining weapons from that period of proliferation have become heirlooms. Despite its role in some traditions, high gun ownership is not inherently tied to cultural practice. The most common reason is self-defense.

But even that reason is couched in nationalist-esque tendencies of the Serbian government, and part of the reason demonstrators protest cultural nationalism. With present-day Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić “constantly telling people we are on the brink of war with Kosovo,” notions of self-defense may be in part synonymous with securitization.

Securitization is a part of the field of international relations. It is the belief that, under the presumption of foreign threats, that the state and people need to increase their own military capabilities to be prepared for the conflict.

And though nothing is concrete about the link to gun ownership and securitization, it’s fairly easy to imagine that some Serbs who buy guns seek self-defense specifically in case war breaks out.

It should be noted that Serbia’s gun control measures are already fairly strict. However, many buy their guns illegally. Of course, it’s nothing decisive, but the commonality of illegal firearm purchases suggests people think of it as a necessity. And securitization, driven by fear, is something that may drive this feeling of necessity.

Ultimately, nationalism has a few key effects on the development of the culture of violence. The contemporary Serbian government considers Kosovo to be rightfully Serbian land, part of nationalist prioritization of territorial integrity. Consequent government fearmongering caused potential securitization in Serbia, arming the population enough for a high risk of shooting.

In Kecmanović’s case, his father owned the guns for recreational purposes. Investigation into his role in the story is still ongoing at the time of writing, so I cannot conclusively say whether his ownership was guided by the speculative securitization. In general, though, his ownership of weapons is certainly part of a broader Serbian gun culture that has a relationship with 1990s weapons proliferation.

Serbian nationalism was also, in part, responsible for the Yugoslavian Civil War. During this period, weapons proliferated as militaries and paramilitaries became prevalent, and since many of those militants are still alive today, they have a profound impact on the life of Serbian youngsters. For example, Blažić’s family consists of heavily armed former army-men, exposing him to beliefs of pro-violence nationalism.

Additionally, nationalism in 20th century Serbia created mass instability in Serbia, which resulted in a vacuum where gangsters, like Golubović and many others, could consolidate power by means of violence. Mobsters are often idolized in the media. Therefore, it’s a major target of protestors alongside certain government figures.

Violence in Media

Reality television, especially those broadcasted on pro-government media, has portrayed the daring tales of gangsters and war criminals. These stories are based on real life paramilitary figures and mobs. They gained their renown during the nationalism-propelled Yugoslavian Civil War, where organized crime and military credibility were the only ways to gain any wealth.

The mobster lifestyle, marked by its participants’ powerful resolve in trying to get a leg up in the tumultuous wartime society, offered a sense of action to relaxed Serbian households after the advent of reality TV.

Over time, some of Serbia’s largest channels began depicting criminal life. What’s worse, many of these shows employ genuine criminals to play themselves.

However, reality TV isn’t the only way criminals are idolized. Documentaries about the era have underscored the lives of people like Kristijan Golubović and many others. Golubović in particular gained much of his fame after his criminal career because he was reputed to be the only surviving gangster depicted in one documentary, generating rumors of his resilience.

So when protestors attribute youth opening fire to violent media, they are at least partially correct. We cannot assume this would be the case, but if the media did not host people like Golubović, it may well be true that Blažić would have been exposed to less violence growing up and therefore would not have committed the shooting. But again, Blažić does come from a military family. It is possible that his military background provided the appropriate environment for his violent tendencies, especially given that many military families were active in the nationalist wars of the 1990s.

A final concession I should make: a lot of the protests use speculation to link media to certain instances of violence. But it’s also evident that nationalism, in the form of ethnic tensions, plays some role in those events. It is a complicated issue with many factors, so it’s best to refocus on the current protests.

Protest and Response

The protests over the shootings have been the largest in Serbia in over 20 years, and they’re outclassed only by the demonstrations that overthrew Milošević in 2000. Serbia Against Violence’s core demands surround the resignation of certain political figures and the closure of violence-propagating media outlets. Aleksandar Vulin, Branko Ružić, and Bratislav Gašić and of course Aleksandar Vučić have been the main targets in the government, and Pink TV and Happy TV the main targets in the media.

Vulin, the director of Serbia’s Security Intelligence Agency (BIA), has come under fire for failing to prevent the shootings. Because he commands the nation’s most powerful enforcement agency, protestors hold him accountable for not stopping the shooters. Vulin was also a strong supporter of Milošević during his reign and a noted nationalist. Alone, this does not indicate anything conclusive, but is interesting given that he seems to have enabled these violent outbursts.

Ružić was the Minister of Education in the shootings and a proponent of Milošević’s Socialist Party. Pressures against him swelled after his official statement blaming “Western values” and video games for the school shooting, culminating in his resignation. This represented a major concession by the government during the demonstrations, coming only three days after the Mladenovac and Smederevo shootings.

Gašić, the Interior Minister, is less controversial, but calls for his resignation are pervasive. He is targeted for his primacy in the Ministry of the Interior, the body responsible for crime prevention, investigations, and counter-terrorism. Protestors argue that the shootings represent a failure of the ministry to perform its duties, and as its minister, he should be held responsible for those failures.

Vučić, the Serbian president and former president of the Progressive Party (SNS), was the most pressured to resign. He has since stepped down from his presidency in the SNS. Vučić is another strong nationalist and populist, and some protestors blame him for fostering a divisive cultural environment that “indirectly led to the mass shootings.”

Protestors also call for the confiscation of Pink and Happy TV’s licenses, a change that would come alongside the prohibition of gang-centered reality shows. Many demonstrators believe the drop in media violence would result in a decrease in violent tendencies overall.

But the government response itself has been discouraging. Coupled with pro-government media denouncing protestors, President Vučić himself has demonized them as “hyenas and vultures” that want his head. Vučić seems extremely unwilling to compromise with Serbia Against Violence.

The protests and their responses are remarkably forward-thinking despite Vučić’s indifference. Compared to the United States, where mass shootings are common — more than 330 with nearly 40,000 casualties this year alone so far — public outrage is massive in Serbia. There has been a robust and cohesive effort to reduce violence after two in Serbia, whereas in the States, a similar “culture of violence” is dismissed as necessary for our gun rights. Furthermore, though Vučić strongly opposes the protests, he’s granted Serbia Against Violence their right to assembly without any sort of violence from police. But back in the States, mass protests about violence, like Black Lives Matter, are usually met with violence as a quelling mechanism.

Serbia Against Violence highlights how American politicians rarely acknowledge shootings. Vučić’s response is disheartening, but negative attention is better than none at all. Policy proposals and vows to the public made by American politicians rarely see their fruits. Their statements are typically empty promises of a safe and secure future.

The United States would benefit from the sort of public attention towards shootings that Serbia is experiencing now. The Serbian people are exhibiting strength in numbers, directing massive upset over the shootings for constructive change. In the United States, this type of already uncommon attention is ephemeral at best. But with the same sort of drive that Serbians are expressing, Americans too can agitate for change.

It is all a matter of protesting loud enough to be heard, and then some. Despite its rigidity, the Serbian government seems to be buckling under the pressure from the demonstrations.

With Serbia in mind, let us look to a future of globally decreased violence.

Closing Thoughts

I started this discussion about Serbia because of how often Central and Eastern European countries tend to be left out of mainstream discussions. It turns out they too, along with the rest of the unheard world, have much to offer to solve the problems that more mainstream countries tend to face.

The obvious example above would be gun violence, where mass demonstration can bring beneficial change. If this happens in Serbia, why not in the United States? Or anywhere else where this issue is pervasive?

Even more intriguing is the histories that build up to events like the Belgrade shootings. Especially in American curricula but even in those of many Western European countries, Central and Eastern Europe are frequently overlooked. It is no help that many of these countries are typically characterized by their conquest by the Soviet Union, stripping their people and cultures of any sort of individuality.

Serbia is one of the region’s many countries with a complicated history. Genocide, nationalism, invasion, populism, and so much more are all deeply intertwined within its story. With this article, I hope to use Serbia as a starting point for a much broader curriculum-development project that brings Central and Eastern Europe to light. In the sidelines of the modern world, we can find inspiring victories buried under unheard tragedies.

On behalf of the Forgotten Europe Project,

Rittik Bhattacharya Curriculum Team Lead at the Forgotten Europe Project

References

Alam, Handay A., Jessie Yeung, Alex Stambaugh, Vladimir Banic, and Josh Pennington. 2023. “Suspect arrested after eight killed in Serbia’s second mass shooting in two days.” CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/04/europe/serbia-shooting-dubona-intl/index.html.

Amnesty International. 2020. “US law enforcement violated Black Lives Matter protesters’ human rights.” Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2020/08/usa-law-enforcement-violated-black-lives-matter-protesters-human-rights/.

The Associated Press. 2023. “Tens of thousands march against Serbia’s populist leadership following mass shootings.” NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/05/13/1175990505/thousands-march-against-populist-leadership-serbia-mass-shooting.

B92. 2023. “Boy called the police after the massacre: I’m Kosta Kecmanović, I shot several people.” B92. https://www.b92.net/eng/news/crimes.php?yyyy=2023&mm=05&dd=03&nav_id=115891.

CBS Baltimore Staff. 2023. “Teen killed, 6 injured in mass shooting at Salisbury block party.” CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/baltimore/news/salisbury-maryland-block-party-mass-shooting-teen-killed/.

CBS News Staff. 1999. “Milosevic: Serb Strongman And Dictator.” CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/milosevic-serb-strongman-and-dictator/.

Delauney, Guy. 2023. “Serbians hand in guns and question culture of violence after two shootings.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-65597622.

Engelbrecht, Cora. 2023. “What’s Behind Serbia’s Gun Violence.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/05/world/europe/serbia-gun-violence.html.

Eroukhmanoff, Clara. 2018. “Securitisation Theory: An Introduction.” E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2018/01/14/securitisation-theory-an-introduction/.

Faguy, Ana. 2023. “U.S. Sees Record Number Of Mass Shootings Halfway Through 2023.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/anafaguy/2023/07/03/us-sees-record-number-of-mass-shootings-halfway-through-2023/?sh=193c20d0360f.

Gec, Jovana. 2023. “Serbians mourn mass shooting victims.” The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/may/07/serbians-mourn-mass-shooting-victims/.

Greenawalt, Alexander. 1999. “Greenawalt: Kosovo Myths.” York University. http://www.yorku.ca/soi/Vol_3/_HTML/Greenawalt.html.

Higgins, Andrew. 2023. “After Mass Shootings in Serbia, Few Are Ready to Give Up Their Guns.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/02/world/europe/serbia-shootings-gun-control.html.

Jozwiak, Rikard. 2023. “Thousands Protest In Serbia, Accusing Government Of Fostering Violence.” Radio Free Europe. https://www.rferl.org/a/serbia-protest-government-violence/32443274.html.

Keskin, Recep. 2003. “The dispute between Bosnian Muslims and Serbs.” Theses Digitization Project. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3316&context=etd-project.

Lapping, Brian, and Nicholas Fraser, executive producers. 1995. Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation. BBC, 1995.

Lopez, German. 2018. “America’s love for guns, in one chart.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/2018/6/21/17488024/gun-ownership-violence-shootings-us.

MacDowall, Andrew. 2018. “Kosovo Serb politician Oliver Ivanović shot dead outside party headquarters.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jan/16/oliver-ivanovic-serb-politician-in-kosovo-shot-dead.

Milenkovic, Aljosa. 2022. “Serbia’s President Aleksandar Vucic will ‘protect our people’ in Kosovo as tension rises.” Europe. https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2022-08-22/Serbia-says-it-will-protect-our-people-in-Kosovo-as-tension-rises-1cHQUuScWcM/index.html.

“Određen pritvor do 30 dana ocu dečaka koji je ubio devet osoba u beogradskoj školi.” 2023. Radio Slobodna Evropa. https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/odre%C4%91en-pritvor-do-30-dana-ocu-de%C4%8Daka-koji-je-pucao-u-%C5%A1koli-na-vra%C4%8Daru/32398798.html.

Ozturk, Talha. 2023. “Serbian police arrest suspect in shooting, killing 8 people overnight.” Anadolu Agency. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/serbian-police-arrest-suspect-in-shooting-killing-8-people-overnight/2889777.

Pinchler, Robert, Hannes Grandit, and Ruža Fotiadis. 2021. “Kosovo in the 1980s — Yugoslav Perspectives and Interpretations.” Comparative Southeast European Studies 69, no. 2–3 (November): 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1515/soeu-2021-0059.

Politiko. 2023. “”He played violent games with his friends and admitted that he was a psychopath”, shocking details of the 14-year-old who killed students in Serbia.” Politiko.al. https://politiko.al/english/rajoni/luante-lojera-te-dhunshme-me-shoket-dhe-pranoi-se-ishte-psikopat-detaje-t-i481542.

Roussi, Antoaneta. 2023. “Thousands protest ‘culture of violence’ in Serbia.” Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/serbia-culture-of-violence-protests.

Sekularac, Ivana, and Branko Filipovic. 2023. “‘Vucic out’: Serbian protesters keep heat on government.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/vucic-out-serbian-protesters-keep-heat-government-2023-06-17/.

Stojanovic, Dusan, and Jovana Gec. 2023. “8 fatally shot in Serbia town a day after 9 killed at school.” AP News. https://apnews.com/article/serbia-shooting-school-belgrade-guns-523b9bf8fdc0e89778baf0d8859401bf.

Vasovic, Aleksandar. 2023. “Serbians rally against violence after two mass shootings.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/after-two-mass-shootings-serbians-rally-against-violence-2023-05-08/.

“Violent Serbian reality TV targeted after shootings: ‘I want it banned.’” 2023. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/world/europe/article/3220343/i-want-it-banned-violent-serbian-reality-tv-targeted-after-shootings.