Why "Central-Eastern Europe?"

Why we use the term "Central-Eastern Europe" instead of "Eastern Europe" simply

The term “Eastern Europe” is one that has evolved and adapted over history in the face of changing social and political climates. Categorizing the region that was once under the Soviet sphere of influence has become a contentious subject of many historical and ethical debates. Moreover, “Eastern Europe” as a term imposed a generalizing Eastern identity upon the many unique and diverse nations and people that occupy the region. It is this debate and resulting ambiguity that has left geographers, historians, and diplomats divided on the question: what do we call post-Warsaw Pact states? Since the collapse of puppet-regime communism in the former Eastern Bloc, many states along the Soviet Bloc’s western border like Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia have been committed to redefine their identity, both to their own respective populations and to the international community. These efforts have resulted in the creation of a counter term—Central Europe. Both “Central Europe” and “Eastern Europe” as terms influence and define the mental map that individuals have of European nations, identities, and categorizations. Ultimately, we must ask ourselves: how should we label and describe a region that is diverse in its peoples, histories, geographic features, and political systems? This short article will not only seek to examine why the term “Eastern Europe” is obsolete but will additionally support the popularization “Central-Eastern Europe” as a term to take its place.

Historical Understandings

It is important to understand the label “Eastern Europe” as one that is grounded in the imperialist and colonialist nature of Western European states. Coined by German nationalists at the Frankfurt Parliament of 1848-1849, references to a perceived “Eastern Europe” were discussed in expansionary and imperial terms. Only some 50 years earlier had the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth been partitioned between the powers of the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Prussian Empire. What ensued was a policy of Germanization with the sole goal of eradicating and assimilating the commonwealth’s diverse population into the German state’s imperial hierarchy. Bismarck’s cultural war against the Catholic Church adopted an anti-Polish tone that targeted the rights of Poles in his new empire. Dreams of prosperity were focused solely on the German people, not the empire’s many new “Eastern” constituents.

Returning to Germany’s parliament of 1848, the term “Eastern” was specifically engineered to demarcate the people of the former commonwealth from their counterparts in the west. Comparative analysis with contempt towards Catholics and Slavs that Bismarck and German politicians expressed reveals the derogatory implications of the label. Imperialists viewed territories east of the German state as a conglomerate mass of land and people destined for colonialization. The term generalized diverse ethnic and linguistic groups into a category that represented inferiority. This is exactly what imperialists needed to justify the vast Germanization and civilizing mission that erased cultures, peoples, and societies. Moreover, the term implies that the European continent is stratified into a hierarchy that places “Eastern” people below “Western” people. Thus, the word “Eastern Europe” should be understood as anti-Slavic and nationalist in nature by specifying a diverse region’s people as subordinate and destined for subjugation.

Justifying colonialism this way is not new by any means. European powers have over centuries embraced nationalist and social Darwinist rhetoric. Almost always, its utility was to justify the subordination, assimilation, or extermination of colonial populations. Yet if the logic of imperial states was often justified by pseudo-sciences like social-Darwinism, then how was colonialism justified when advanced against neighboring European states? In the case of the Commonwealth, the Slavic people became “white, but not white” to imperial powers. Slavs were degraded to a sense of European other that the term “eastern” became synonymous with. These nationalist tactics painted whiteness as an ethnic value that—while distant for Slavic people—was attainable through the processes of Germanization and cultural eradication. The resulting implications for people of color both in and beyond the region were devastating. Empires painted whiteness as an idealized trait that was impossible for people of color to attain. The mistreatment and genocide of the Roma people by Prussian and Nazi governments best encapsuled these attitudes. These legacies continue to haunt the many millions of Roma people in Central-Eastern Europe today. Labeling groups of people as “Eastern European” historically idolizes whiteness and western identities, debasing and discriminating against billions globally. While it is impossible to compare experiences with imperialism in Europe to that of other continents, lessons and similarities can be drawn from both; The term “Eastern European” is no exception to such comparative analysis.

The historical recency in these developments is yet another example of how the term eastern was one specifically used by imperialists. Two centuries of imperialism have otherized Central-Eastern Europe to be separate and below the West. Before the 19th century, the Commonwealth’s success as one of Europe’s largest land-based empires placed it at the forefront of European politics, developments that are unfortunately omitted from mainstream history. The historical recency of the term “Eastern Europe” implies that imperialists disregarded centuries of history for the purpose of promoting colonialism. Eradicating memories, understandings, and knowledge of the region’s various successes in history helped empires attack Central-European national identities. The goal was to erase all senses of national pride and belonging. Consequentially, “Eastern Europe” became a blank canvas for imperialists to paint German history, culture, and civilization. Fortunately, the emergence of independent nation-states after World War I proved that such a strategy failed; However, the role that historical erasure played should not be ignored. The German state’s rendering of “Eastern Europeans” as a faceless and cultureless group of barbarians is often felt today. Modern stereotypes of “squatting Slavs” that portray Central-Eastern Europeans as uneducated and impoverished epitomize how the region’s history has been effaced and forgotten. For many western audiences today, the word “Slav” and “Eastern Europe” is first associated with a stereotype, not a rich history.

Fortunately for these forgotten peoples, World War I sparked the collapse of some of these western European subjugators. States like Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia—then the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes—were liberated from German and Austro-Hungarian imperialism. These new states struggled to redefine their identities on the European map. Thus, these new states adopted post-colonialist nationalism to guide industrialization and modernization, key to stay competitive on the European canvas. In the postwar period, these states distanced themselves from the German and Russian—now Soviet—markets after a century of subjugation. Postwar inflation complicated the process, but regardless these states achieved their economic independence.

Unfortunately, this interwar period was short-lived. As is the case in many collapsed empires, resentment was brewing against the independence of these states. Hitler and the Nazi party’s rise to power is one of the best examples of imperial reification in history. Anti-Slavic and anti-Semitic sentiment became the foundation for Hitler’s perception of the East. These peoples’ sovereignty and mere existences were major issues for Nazi Germany. Such attitudes manifested in the Generalplan Ost to starve, execute, and ultimately eradicate many ethnicities to Germany’s east. Millions of Poles, Belarussians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and Jews were systematically deported and murdered to make way for German colonization. Even before the war, the Deutsche Arbeitsfront or German Labor Front had devised plans to reorganize Polish lands for the purpose of German expansion. Interestingly, no similar plan emerged for the areas of Western Europe that the Nazi regime had conquered. The German understanding of its eastern neighbors mirrored the otherizing notions left by Prussia in the 19th century. “Eastern Europe” was regarded with a sense of inhumanity and barbarism that only genocide could resolve. Accordingly, this exposition denounces the term’s modern usage, rooted in historical justifications of the region’s imperial subjugation by Western powers.

Current understandings of the word “Eastern Europe” are products of the postwar atmosphere and political environment in Europe. The triumph of American and Soviet armies on opposite flanks of Hitler’s regime solidified the stage for the Cold War. However, ideological differences between the two main victors left Europe in a polarized point of contest between capitalists and communists. Soviet occupation of Nazi Germany’s eastern half transformed the many nations of Central Eastern Europe into puppets of Soviet imperialism. The emergence of communist regimes in these states was a buffer zone engineered by the Soviet Union to protect them from the West. Quite simply, these states served little purpose but to protect the Soviet Union, robbing them of both their agency and safety. Anti-communist political dissidence was persecuted. Democratic elections did not occur until the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union.

It would be egregious to conclude that these states willingly accepted the Soviet presence, much less its oppression. The continued postwar fighting of partisan Żołnierzy Wyklętych or Cursed Soldiers against the Soviet Union illustrates their uncomplacent attitude towards subjugation. Uprisings in Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia between 1950 and 1980 further proved that much of Central-Eastern Europe’s population was more than dissatisfied with the regime in power. Only in the 1980s were various peaceful revolutions finally able to topple the Warsaw Pact’s communist regimes.

The label “Eastern Europe” became synonymous with the social and political climate that these puppet states endured throughout the Cold War. It was used to separate these nation’s experiences from the growth that much of Western Europe enjoyed at the time. Concerningly, the term’s modern usage implies that communism’s totalitarian conditions still exist in these nations. Since the political revolutions of the 1980s, these countries have adopted democratic political systems, privatized economies, and to some extent, Western cultural values. Most of these states have become stalwart allies to their former Cold War adversaries with many among them joining both the European Union and the North Atlantic Alliance. Understanding these nations as politically Eastern is an erroneous assumption at best. More importantly, the label becomes derogatory because it subscribes these states to their brutal experiences with centuries of subjugation by both Western and Soviet imperial powers.

Geography

The problem this short work addresses, is the continued use of Eastern Europe as terminology for the states east of Germany at official level. The terminology’s history has clearly outlined it as a pejorative, one that states have used to justify expansion, colonization, and genocide in the region. Then why do organizations like the UN still refer to that portion as “Eastern Europe?” It is impossible to answer this question without factoring in the historical forces of the Cold War. Large organizations continue to use this term because understandings of the European continent continue to be rooted in the division between east and west. Slavic and Baltic people have been simplified to the eastern political designated based on conditions that ended over 30 years ago. The term is obsolescent, and change is needed.

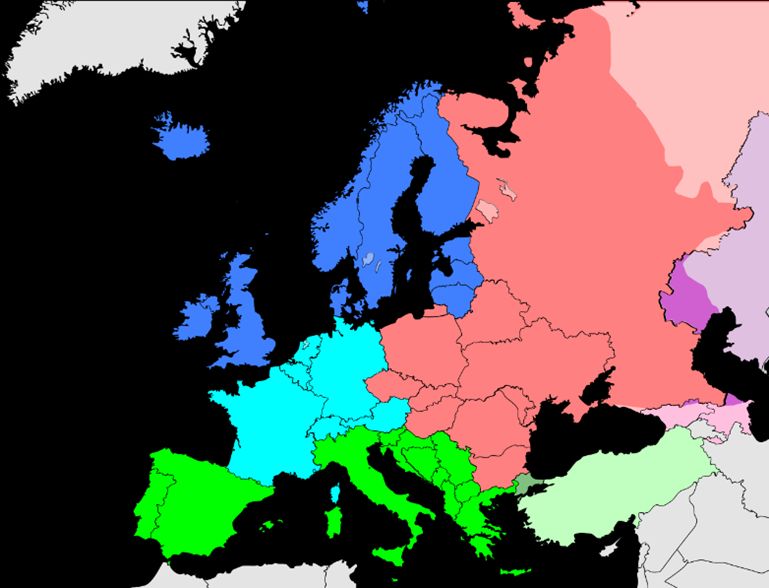

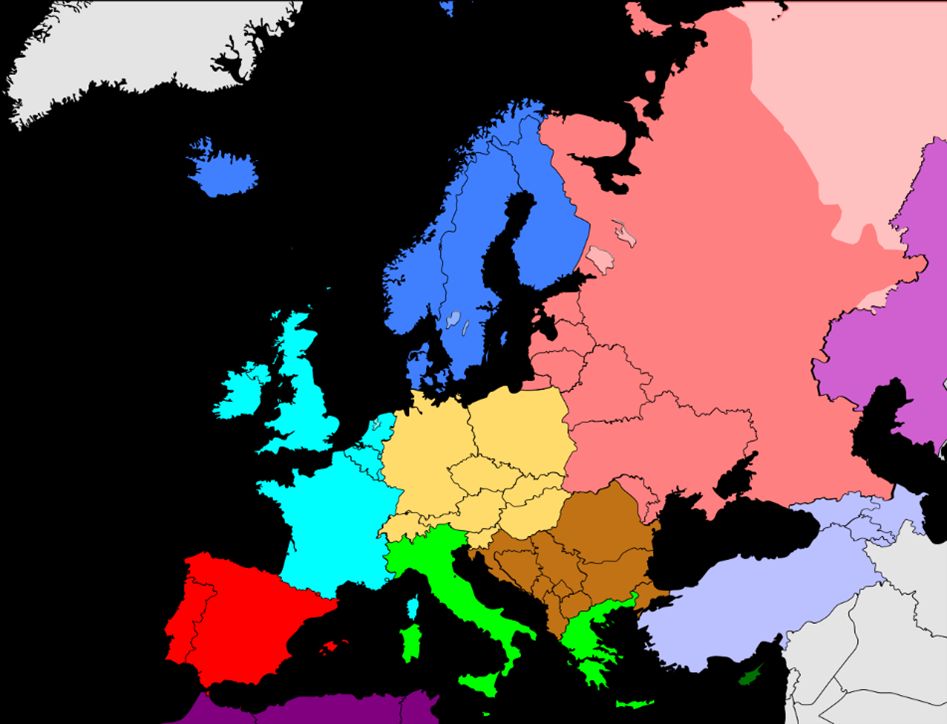

The defining characteristic behind the use of” “Central-Eastern Europe” as a category is its basis on geography, not subjective social or political assumptions. This serves two purposes: to categorize the region based on objective physical attributes, and to distance these nations from the aforementioned memories of Soviet repression. The solution this paper presents in the form of the label “Central-Eastern Europe” is political neutrality. More importantly, our new term distracts away from the divisive subjects that have left the region conflicted and polarized. Religion, politics, language, and alphabets are only a few of the many hallmarks that made the issue of western versus eastern identities so striking. The CIA world factbook circumvented this divisive duality by organizing the region into sub-categories—notably Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Southeastern Europe. This interpretation of the European mind map achieves both of our previously mentioned goals. Each category is based on the relationship between a state’s geographic positioning in relation to the European continent. Consequentially, these states are freed from the derogatory implications that being an “Eastern European” entailed.

While effective at avoiding the contentious Cold War issue, this interpretation does not provide a single designation for post-Warsaw Pact nations, the goal of this paper. Such a framework makes references to these states as a collective impossible. Thus enters our new term, “Central-Eastern Europe”. The European Union is the largest international organization to classify European nations this way.

When referencing the many nations that endured the collapse of communism, this appears to the most inclusive of the region’s many polarizing values. Conversely, the CIA’s methodology visibly focuses on a more specific and localized geographic standard than Eurovoc’s. That is not to say that the Union’s interpretation is geographically invalid, however. The term Central-Eastern Europe describes a series of nations that, in relation to the entire European continent, are longitudinally central and eastern. Simultaneously, including the word “central” into the category’s name removes any isolation that eastern politics in the past had developed. This designation neutralizes the polarization between east and west and accepts the region’s diversity.

Conclusive Thoughts

Looking back upon the history of Eastern Europe as a term, it has never been used in a positive context with its constituents. From an origin in Prussian imperialism, to modern usage that reflects Cold War sentiment, being Eastern European was symbolic of inferiority, and more importantly, a sense of otherness. Historical studies trace the term to be one that is forced from colonizer onto the colonized. Only states in Western Europe that have not endured the same adversity refer to these nations as Eastern, alienating them in the process. The ramifications are all negative, leading to disunity, separation, and prejudice on the European continent.

The implications of transitioning to the use of Central-Eastern Europe in diplomatic and social spheres touch on all the values this exposition has promoted. Foundationally, this terminological transition is a promise of respect to the nations that the label describes. Respect for their diverse position as the boundary between east and west, respect for their relationship to the Cold War, and ultimately respect for each nation’s respective identities. For many of these states, that choice has been to be part of Central-Europe. For others, the term Eastern Europe appears appropriate. Combining both these choices into one term thus respects and includes every nation’s decision. It is the responsibility of individuals, discussions, international organizations, and whole societies to uphold that respect.

Works Cited

CIA World Factbook. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2010.

“The Creation of the Soviet Buffer Zone.” The creation of the Soviet Buffer Zone - the Cold War (1945–1989) - CVCE website. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cvce.eu/en/education/unit-content/-/unit/55c09dcc-a9f2-45e9-b240-eaef64452cae/a813e2e2-d50d-4f1f-a31b-0ffe5f2c169b.

“Definition of Regions - United Nations.” United Nations. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://esa.un.org/MigFlows/Definition%20of%20regions.pdf.

“Eastern Europe.” Visit the main page. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Eastern_Europe.

Eurovoc. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1987.

Fenwick, Charles. “Jugoslavic National Unity : Fenwick, Charles G. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, November 1, 1918. https://archive.org/details/jstor-1945848.

Fernandez, Unai. “The Nazi Anti-Urban Utopia: ‘Generalplan Ost.’” M, September 3, 2018. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/5117/511767145006/html/.

“Germans and Poles: Despair and Hope.” Deutsches Historisches Museum berlin - germans and Poles - 1.9.39 - despair and hope - exhibition. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.dhm.de/archiv/ausstellungen/deutsche-polen/en/germanisierungspolitik.html.

Morawski, Wojciech. “Post-War Economies (East Central Europe).” Encyclopedia 1914-1918, January 4, 2017. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/post-war_economies_east_central_europe#:~:text=After%20World%20War%20I%2C%20five,Latvia%2C%20Lithuania%2C%20and%20Poland.

office, Kafkadesk Kraków. “Who Were Poland’s ‘Cursed Soldiers’?” Kafkadesk, June 28, 2023. https://kafkadesk.org/2022/02/27/who-were-polands-cursed-soldiers/.

Petersen, Hans-Christian. “Between Marginalization and Instrumentalization: Anti-Eastern European and Anti-Slavic Racism.” illiberalism.org, November 18, 2022. https://www.illiberalism.org/between-marginalization-and-instrumentalization-anti-eastern-european-and-anti-slavic-racism/.

Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, 2022.

Spear, Stephen. “TEACHNYPL: The Role of Social Darwinism in European Imperialism (Gr. 9-10).” The New York Public Library, May 2, 2016. https://wayback.archive-it.org/18689/20220313040506/https://www.nypl.org/blog/2013/10/15/classroom-connections-social-darwinism-european-imperialism.

Szlanta, Piotr. “Polish Roads to Independence.” Niepodlegla. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://niepodlegla.gov.pl/en/-niepodlegla/polish-roads-to-independence/.

Trachtenberg, Marc. A constructed peace the making of the European settlement, 1945-1963. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1999.

“UNSD — Methodology.” United Nations. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/.

Wolf, Gerhard, and Wayne Yung. Ideology and the rationality of Domination: Nazi germanization policies in Poland. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2020.